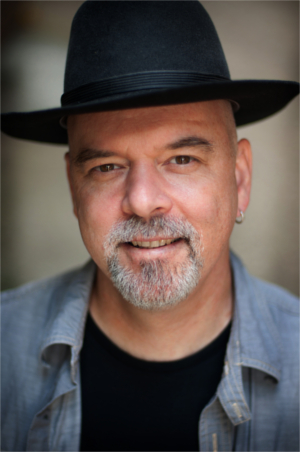

Interview with Broken Age Composer Peter McConnell

Composer Peter McConnell discusses his work on Broken Age and his many collaborations with Tim Schafer dating back to LucasArts. Peter has also composed for non-adventures including many of the Star Wars games and Hearthstone.

You’ve likely heard his music in video game mega hits such as Sly Cooper or Plants vs. Zombies, but you probably didn’t know that music composer Peter McConnell was fundamental in adventure game history. Peter McConnell was an early employee of LucasArts and eventually went on to compose for countless adventure game masterpieces within the company, such as Grim Fandango, Day of the Tentacle, and Monkey Island 2. He’s returned to his roots, teaming up again with longtime-collaborator Tim Schafer for the second installment of the highly anticipated adventure game Broken Age: Act 2. We managed to catch up with McConnell and hear his thoughts on the creative process, as well as some compelling insights on the world of video game composing in general.

JA: You have an extensive, impressive career of composing for many highly recognized video games: Sly Cooper, Grim Fandango, and Psychonauts, to name a few. Many of these titles, including the highly anticipated Broken Age: Act 2, had you working beside game design icon Tim Schafer. Is there something about working with Tim Schafer that has you constantly returning as a collaborator?

Peter: It’s no secret that Tim is the very best at what he does. I was fortunate to work with him from very early on at LucasArts and honestly, I can’t explain why the collaboration works so well. Perhaps part of it is his love for, and extensive knowledge of, music. Also in my experience, Tim has a fine-tuned sense of how much to be involved in what the others on his team are doing, leading more by example and suggestion than by direction. In that way he brings out the best in his team and inspires loyalty over the years.

JA: You have a significant history of working on adventure games; co-inventing the iMUSE interactive music system for LucasArts and working on classic titles such as Monkey Island and The Dig. You’ve also composed for many non-adventures such as countless Star Wars games and Microsoft’s Kinectimals. How do you feel — if at all — soundtracking for adventure games differs from composing for something like a FPS or an arcade title?

Peter: First I would say the similarities outweigh the differences, since the different kinds of games can have similar emotional situations, and in the end, emotion is what we score. But because adventure games have so much dialogue, I think they’re a little more like movies than other games are. A great deal of movie scoring has the job of emphasizing the emotion in conversations between characters. In that way, I think you could call adventure games more “cinematic.”

JA: How do you feel about the current state and future of adventure games? Is it a genre with which you hope to continue involvement?

Peter: I’m very excited that there is so much interest in adventure games these days. I think that as the game audience broadens, more people are becoming interested in interactive experiences that aren’t necessarily focused on high action. The irony is that adventure games started out as a niche market of geeks, and it’s now accessed by a new, wider mass audience that is helping to bring them back.

JA: Your soundtrack for Broken Age has a somewhat classical feel. Given your dynamic discography of many tones and themes, I imagine you’ve written many traditional and non-traditional styles of music. Was writing for Broken Age more prone to your personal style? Has there ever been a particular title you felt really took you outside of your comfort zone, or have all of the titles you’ve worked on challenged your musical instinct on some level?

Peter: I have pretty broad musical tastes and have developed a love for many kinds of music, perhaps from having lived in a lot of places growing up. I’ve been lucky in that each of the diverse titles I’ve scored – games such as Grim Fandango, Sly Cooper, Brutal Legend, Broken Age and Hearthstone – has allowed me to tap into some part of my musical self. So it’s not a matter of being inside or outside of my comfort zone; instead it’s finding that part of each project’s musical world that resonates with what’s already inside me.

JA: What kind of influences did you bring to Broken Age? How much of that influence came from the direction of the game staff and how much of it came from your own personal ideas?

Peter: A lot of Stravinksy, surprisingly. Or maybe not surprisingly, since the Rite of Spring touches on similar themes. That influence was something I brought to the table. I had pretty much a free rein from Tim and the team. Camden Stoddard, the lead sound designer, is a great music editor, and his choice of temp music for some of the scenes really helped me to get the mood right, especially early-on in the game.

JA: Do you feel your calling has always been composing for games or have you always wanted to compose for other mediums as well?

Peter: I think my calling has always been music. I find that I’m particularly suited to music for games because I like the way different parts of the score can connect to each other in an interactive setting. When I was a kid I always came up with soundtracks in my head to accompany my pretend play. It’s not much different now, except that I get to hear the soundtracks played by a real band or orchestra.

JA: Of all the titles you’ve composed for, is there a recent game that you were particularly attracted to as a player rather than composer? How involved are you usually with playing the game, both during and after development?

Peter: Most recently, Broken Age and Plants vs. Zombies 2. When a game is in development I usually don’t get a lot of chances to play because it’s not practical to get a PS4 or Xbox title that’s constantly changing out to the composer. So we often have to rely on Quicktime videos of gameplay. With Broken Age I had a whole development system for the game on my laptop, and I was able to do a lot of testing and even some implementation directly on my system. PVZ2 has a pretty short turnaround time between each new installment, and I can experience the results of my work pretty quickly.

JA: What advice would you give to aspiring game composers, such as myself? Do you feel there are facets of the game industry that provide musicians with more opportunities than ever before? Or do you feel there are more hurdles than ever?

Peter: Both. There are more hurdles because the stakes are so high for big titles. At the same time, there are more opportunities because the industry is so big. Most people scoring Triple A titles have agents and years of credits behind them. But there’s a new mobile game made every day, and there’s always the chance that it could be the next Angry Birds.

JA: Adventure games are constantly forwarding interactive narratives through its medium’s advancing technologies. Have any new technologies influenced the way you compose today?

Peter: Honestly, I can’t think of anything that has had a huge impact lately. There are small things – for example, I like the way written music is more easily integrated into modern DAWs (Digital Audio Workstations). That not only makes it easier to pay attention to the details of how the parts of a piece work together; it also streamlines the process of getting orchestral music ready for orchestration. But in terms of game technology, I haven’t seen anything that affects the way I write music as much as some of the things we did in the mid-to-late 1990s. That was when our in-house system allowed us to easily mock up the way an entire score fits together, with all its transitions, and it was a big help in writing Grim Fandango. I don’t know of any off-the-shelf tools that do that sort of thing now.

JA: For Broken Age there are very orchestral sounds, such as Battle at Shellmound, as well as some keyboard electronic elements such as Walk Under the Stars tossed into mix, . What actually is the process in working on a game like Broken Age? Do you have to bring in a collective of musicians, or is most of it achieved singlehandedly?

Peter: Walk Under the Stars has some keyboard and electronic sounds in it, but it’s mostly a live sextet: violin, viola, cello, clarinet, bass clarinet and flute. All the parts were recorded at the same time at Pyramind Studios in San Francisco. That allowed us to get a nice ensemble feel with the piece. At the same time, the electronic sounds help to suggest the lonely world of the boy’s spaceship. You could think of it this way: the electronic instruments are the boy’s environment and the live instruments represent his emotions.

The sound of Shay’s spaceship music was one of the easier things to develop during the process of scoring the game, because the spaceship is a contained and intentionally uniform environment. Vella’s worlds, on the other hand, are more expansive and varied, and thus more difficult to score. You also deal with constraints: at the beginning of the project there was no hint of a possibility that we might be able to use a live orchestra, and I didn’t want to use orchestral samples. But then, many months into the project, the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra came into the picture and the score expanded in scope and ambition. So the process evolved over time and included a fair bit of luck.

JA: In Broken Age, was composing any particular piece really memorable?

Peter: Probably the opening hillside music, because it went through a number of changes, first sounding like a sort of Northern European seaside song with just a very small ensemble. Then Tim said he didn’t want it to sound too specifically cultural, or “too Renaissance Faire,” as he put it. When I heard the voice parts and some of Camden’s temp music, it became clear that the emotion in the scene was bigger and more timeless, so the orchestra was the way to go. By the way, the opening became one of my 8-year-old daughter’s favorite pieces of music, and she learned to play it on piano. The version on the OST doesn’t actually appear in the game, but is edited together from a couple of the cues – and that’s the version my daughter learned to play.

JA: How much influence does player interaction have on your compositions? Do you rely on developer or player input for certain musical cues?

Peter: You always have to put yourself in the player’s shoes. That’s what made it so useful to have the entire development system for the game on my own PC.

JA: Is there any avenue of the game industry you’re particularly excited about right now?

Peter: I like the resurgence of adventure games, because it means that story is becoming important again. I also like the success of the new generation of large consoles, because that means people care about production values.

Leave a Reply