Interview with Bill Tiller

Bailey James speaks with the artist/designer of Duke Grabowski, the Monkey Island series and many other titles concerning the creative process

If you ever think of a pirate and laugh instead of shuddering in fear, you probably have Bill Tiller to thank. He’s one of the creative forces behind the Monkey Island series and has created some of the games’ most iconic visuals and backdrops. By creating original art that lends the games an air of comedy and lightness, Bill has made them instant fan favorites.

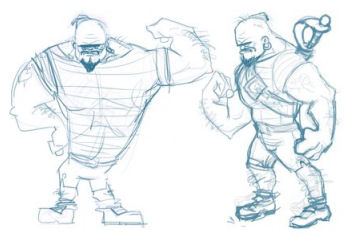

Not yet exhausted of pirates and their woes, Bill spearheaded a new game (which was funded through Kickstarter) that follows a very different kind of buccaneer. Duke Grabowski, Mighty Swashbuckler stars Duke, who’s bumbling and luggish but has a heart of gold. His adventure can be found on Steam and you can read our full review of the game here.

We’re grateful that Bill allowed us to probe his brain for thoughts on the gaming industry and his role in it. Check out his answers below!

JustAdventure: How did you get your start in the industry? Did you always want to do art?

Bill Tiller: I actually studied traditional character animation at a school founded by Walt Disney. Basically, a bunch of Disney artists taught me how to make animated movies. I was more drawn to using the computer for art instead of paper and pencil, but I wasn’t that interested in 3d. I wanted to animate in 2d using Dpaint Animator on the Amiga 2000s we had supplied to us by Disney. I was a bit of an outlier in that way because all my classmates (except Pixar’s Pete Doctor) preferred using pencil and paper. I had owned an Apple II+ PC at home and learned how to make art on it and programmed my own games in BASIC. So I was completely comfortable with the computer.

Since I had a lot of computer art in my portfolio it caught the attention of a lot of game companies, but not TV or movie studios because they weren’t using computers yet. Lucasarts and Broderbund offered me jobs, but Lucasarts attracted me due to the association with Lucasfilm, Star Wars and Indiana Jones. Also, the game I was going to be working on was a Steven Spielberg project so I was hooked. Plus, I had just played Monkey Island 2 and Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis, which I really enjoyed, so I was thrilled with the idea of working for Lucas. I have been working on games ever since.

JA: What is your process when creating game environments?

BT: It depends on the game type. In the case of adventure games first I need a final game design, or nearest as we can get. If I have time I’ll do 6-10 rough small drawings called thumbnails in which I try and work out visually how the puzzle will work. I want to stage the layout for the best dramatic effect and want to make sure it functions clearly for the gameplay. I do thumbnail sized drawings for two reasons, the small size is faster, and if the sketch is clear in the small size then it will be even clearer, and better designed, when redrawn at a large size. It’s kind of like logo design, you want a logo that is clear and visible no matter how small it is. Then I do a bigger sketch based on the thumbnail. This time I add more details. I keep this sketch rough too so I can work out the shapes without worrying about the clarity or details.

|

|

I then do a final line drawing over the rough sketch. This line drawing is what we use in the game until the final color is done. It’s a good way to test out my layouts and discover problems before I commit to final art. The lines act as precise borders for when I do the final color rendering. I can’t change the shape of things in the color layer or it will screw up the scene that we have scripted together. Making changes to the line drawing is a pretty easy way to work out problems with the layout.

|

|

Last step is to paint the image in Photoshop. Since the animation is in 3D we needed to have the character walk around and in front of the art, so I have to paint what we call z-planes on separate Photoshop layers. For example, if Duke is at restaurant, and he walks around a lot of tables, then I have to paint all the tables separately on a layer above the background, and the scripters then place those z-planes of the tables in the scene as flat 3d objects. The table’s z-plane then faces the camera to give the illusion that the table paintings take up real depth in a 3d space. After that I just make minor fixes to any art bugs the scripters or testers find.

JA: When working on the Monkey Island series, did you know from the beginning how playful the world of the story would be? How do you help translate the tone of a game into its art?

BT: Not really. We weren’t sure what art style we were going to use, ultimately. But after a lot sketching and designing we settled on the final look. That all took about three months. I assumed that we’d just try and make the game look like Monkey Island 2, but then it became clear to us that we could make a bunch of positive changes to make the game look even better. This was possible thanks to the significant improvement in PC computing power. The most significant change was in resolution because it was twice as high as the resolution on Monkey Island 2. This higher resolution allowed us to animate in the traditional way with paper and pencil. This meant the characters were going to have traditional cartoon outlines like Maniac Mansion 2: Day of the Tentacle. This was unlike Monkey Island 2, where the resolution was too low to have outlines. Prior to CMI, animation was done using a mouse with Dpaint Animator Software — not the best tools for creating great animation. The number of actual colors we could use for the backgrounds did not change from 256, but we could dither two colors together to make a third because the higher resolution blended the two together. To match the look of the animation we went with backgrounds that had pencil outlines as well.

For fun we decided to make more exaggerated and fun designs for the characters and environment. To help the characters’ personalities pop out, we exaggerated and caricatured their designs. This look was inspired by Art Director Deane Taylor’s work on The Nightmare Before Christmas and other avant garde animation at the time like Ren and Stimpy, Duckman and classic Warner Bros. cartoons. The colors were inspired by NC Wyeth, Howard Pyle and the Hildebrandt brothers.

JA: What’s the most challenging part of spearheading a new game? Did you face any unexpected setbacks when making Duke Grabowkski?

BT: I find the most challenging aspect of any new game is the technology, and that was true with Duke as well. Although, the tech issue was made a lot easier by using Unity and Adventure Creator. We made some money-saving compromises early on that made things difficult to fix later on. So we didn’t have the problem creating our own engine from scratch, or adopting an existing engine, but we did have trouble making changes to the technology to meet higher quality standards. It’s the same old game of balancing time, budget and quality — that is always the case.

The biggest setbacks were in the animation and rigging. To have a lot of animation we had to use a simple common rig. But the rig we used was pretty restrictive and inflexible for some of the more subtle animation we really wanted to do. I think we needed those subtle elements, so the next models may have to use a more expressive rig.

JA: Beyond the obvious, how is crowdfunding through a platform like Kickstarter different than making games through the studio system? Which do you prefer?

BT: With crowdfunding you get way less money so you really have to pare down the size and quality, and take way more time. When the game is done you still have to create the rewards, which is what I am doing right now, but you do have a lot more freedom.

I prefer the studio system better because you get a lot more help and resources that improve the quality of the game significantly. Your deadlines and budgets come with that upsurge in quality, which isn’t really a bad thing in many ways because you have clear goals and restrictions. So they both have their positives and negatives. I probably won’t do crowdfunding anymore for games, but I would use it for other projects for sure, like art books, comics or animated short films.

JA: One of the things I really like about Duke Grabowski, Mighty Swashbuckler is that Duke is a dynamic character who changes throughout the story. Was that your intent from the beginning? How did Duke complexify as you created the game?

BT: I like to saddle my characters with burdensome flaws they need to overcome, because ultimately that is what most stories are about. Duke’s flaw is that he is slow and naive, way too trusting, but he does have two gifts that he uses to overcome this burden: his innate goodness and his perseverance. I think of him as Huckleberry Finn with muscles. He is insecure and surrounded by scoundrels. He sees them as peers whom he needs to impress, but really he doesn’t belong with them —- he’s too nice and good-hearted to be true pirate SCUMM (™). So Duke starts off thinking he needs to be respected by theses boors, but slowly starts to see them for what they arrrr. He hasn’t fully made the transition yet, but he’s just starting to wake up.

Duke is inspired by Mongo from the Mel Brooks movie Blazing Saddles. Mongo was this caveman-like desperado who is told to kill a whole town, and the black sheriff in particular, but when he is defeated by the sheriff, and is treated nicely, he realizes what real friends look like. It’s a bit similar to Duke in that way, but Duke is a bit smarter, and has a worse temper, and is pretty much invulnerable. Duke would make an excellent linebacker in American football because he has all the traits needed to succeed in that game.

JA: I saw on your Kickstarter that you’re planning on making Duke an episodic character. What do you have planned for him in the future? What kind of adventures do you think he needs to go on to grow as a character?

BT: We want to continue his character arc; starting as an insecure guy trying impress his scumbag friends, to a self-secure protector of his true friends. Duke isn’t quick so it will take a few episodes for him to fully see the right path, and there is a mystery we have set up that Duke will be compelled to follow. He will also have to deal with consequences of his more brutish tactics, and come to realize strength and force aren’t always the best ways to solve problems.

JA: If you could never do another funny pirate game again, what kind of game would you like to design? Or, what’s an art style you’ve never been asked to draw that you’d love to try your hand at?

BT: I would like to make more games with the characters from Ghost Pirates of Vooju Island, maybe do a higher def version of Curse of Monkey Island. But beyond those, and finishing Duke, I think I might be pirated out. I have been jonesing to get back to Draxsylvania, or explore a game that is in the Raygun Gothic setting.

Thanks so much to Bill Tiller for giving us a look into his creative process. As a reminder, you can find Duke Grabowski, Mighty Swashbuckler available for purchase on Steam. You can read JustAdventure’s full review of the game here.

Leave a Reply